Daniel Simon, WLT Editor in Chief

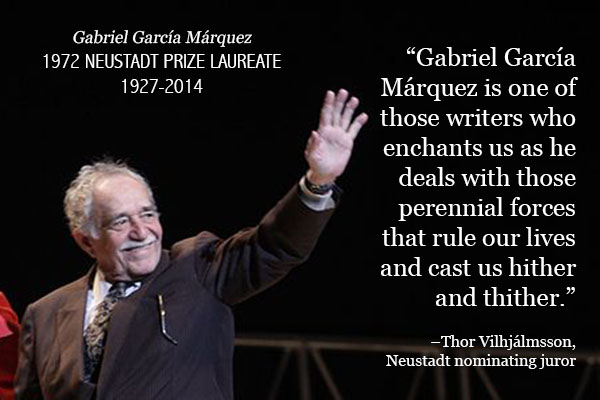

When news broke yesterday about the death of Gabriel García Márquez, the entire staff of World Literature Today paused to reflect on the legacy of a writer who not only redrew the map of world literature but also added a thousand new colors to illustrate its unknown territories. García Márquez received the first of many international awards when he was chosen as the winner of the 1972 Neustadt International Prize for Literature, an award sponsored by WLT, having been nominated by the Icelandic writer Thor Vilhjálmsson and chosen by an international jury from an illustrious slate of candidates that included future Neustadt laureates Paavo Haaviko and Czesław Miłosz as well as Carlos Drummond de Andrade, Zbigniew Herbert, Octavio Paz, and Nathalie Sarraute. The Summer 1973 issue of Books Abroad (the forerunner of World Literature Today) paid tribute to “Gabo” after he visited Oklahoma to receive the Neustadt Prize in June 1973. To add a few grace notes to the chorus of tributes that began pouring in yesterday evening, we’re reproducing below a personal appreciation of García Márquez’s life and work by longtime Books Abroad / WLT editor Ivar Ivask, who inaugurated the Neustadt Prize, and a review of the first installment of García Márquez’s memoirs, Living to Tell the Tale, by Edward Waters Hood. – Daniel Simon, WLT Editor in Chief

Allegro Barbaro, or Gabriel García Márquez in Oklahoma

Ivar Ivask

García Márquez has studied and read more English than French or Italian, yet perfectly fluent in the latter two, he is hesitant to speak English. Why? “Because the English sentence is too simple,” he explains. As to his tastes in music (he is quite a stereo-buff), he prefers the period from the late Beethoven to the last Bartók. He admires in particular Bartók’s way of breaking up the melodious line to which the 18th- and 19th-century masters have accustomed us. There is a lesson here for the modern novelist: “The Spanish prose sentence falls almost inevitably into hendecasyllabic or alexandrine verse which I want to avoid. One of the main tasks in polishing the text of my new novel, ‘El otoño del patriarca,’ a complicated work, will be to break this flow of my sentences. By the way, the double meaning in the English translation of the novel’s title, ‘The Fall of the Patriarch,’ is more apt than the original title but unfortunately cannot be duplicated in Spanish.”

An aversion to simple sentences, a wish to achieve greater rhythmic complexities in the prose of his fiction: it all fits the complicated, intense, cordial character of the Colombian novelist who had come to Oklahoma to accept his prize (see also BA 47, no. 1, 7–16) . He made his stopover of barely two days, 27–28 June 1973, on his way from New York to Los Angeles and from there to a longer vacation with his entire family in Mexico. The best manner of characterizing this brief encounter would be in terms of one of Bartók’s compositions, “Allegro barbaro.” However, for Bartók—one of García Márquez’s most admired human beings—“everything came too late.” Fortunately this is not true in the case of García Márquez, who by 45 has produced a world-wide bestselling novel and was awarded in 1972 both the prestigious Latin American Rómulo Gallegos Prize as well as the Books Abroad / Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

He had come to accept the Books Abroad/Neustadt award at an informal presentation “with an absolute minimum of witnesses.” Crowds and public spectacles frighten him, hence his insistent request that we dispense this one time with a public ceremony. A few sentences were pronounced by Mrs. Walter Neustadt, who presented the symbolic silver eagle feather (in a box made of three woods native to Oklahoma—cherry, pecan and walnut); Huston Huffman, President of the University of Oklahoma Board of Regents, spoke briefly in Spanish and presented the check for ten thousand dollars along with the hand-lettered leather-bound certificate—in the absence of vacationing University president Paul F. Sharp—while thunder and lightning were raging outside and we looked out to see it raining in Macondo. Two photographers illuminated the scene inside. García Márquez’s thanks came later in the form of a short written statement released to the press:

This is a prize that has taken shape in the fertile imagination of a native of Estonia who has attempted to invent—rather than dynamite—a literary prize that would be dynamite for the Nobel. It is a prize in the mythical Oklahoma of Kafka’s dreams and the land of the unique rose rock, and has been awarded to a writer from a remote and mysterious country in Latin America nominated by a great writer from far-off Iceland. These circumstances suffice to make of the Books Abroad / Neustadt International Prize for Literature the one great international prize for highly deserving writers who are not yet well known.

To be quite honest, the image of dynamite and dynamiting never would have occurred to me; it belongs to García Márquez’s own resourceful imagination. Furthermore, since things are not supposed to be too simple, another news release was simultaneously made in New York by García Márquez’s American publishers Harper & Row, explaining that he intends to establish with his prize money a defense fund for political prisoners in his native Colombia.

In retrospect I am still amazed at how many matters we were able to talk about before the presentation! He related to me, for example, that Pablo Neruda, the runner-up for the 1970 Books Abroad Prize, had expressed his great satisfaction to him in Paris about Giuseppe Ungaretti winning our award a few months before his death. What would García Márquez do in Los Angeles? Talk about Ray Bradbury. Science fiction aside, he thought Bradbury had written three or four of the most amazing pages in all modern prose. And Borges had dedicated some of his finest pages to a Spanish edition of Bradbury, as García Márquez informed me, immediately adding: “There are very few authors whom I have read completely; Borges is one of them.” Spending an evening in the company of two poets, my wife and I, it was inevitable that his expressed dislike of—or better, lack of interest in—poetry had to come up. No, it actually was not quite exact, he considered himself a “clandestine poet,” who liked, among twentieth-century poets, most especially Pablo Neruda, Pedro Salinas, Luis Cernuda and Jorge Guillén. What about the roman nouveau, structuralism? A dead end.

So the hours passed, with García Márquez alert to everything: food and wine being served, music in the background, questions about literature past, present and future. Too bad I thought of playing the record with Bartók’s “Allegro barbaro” only long after he had left. By now he is surely in Mexico, where his sons Rodrigo and Gonzalo were born, trying to break the backbone of the all-too-natural Spanish prose sentence. But how can you possibly turn the noun “otoño” of Latin origin into anything resembling the Anglo-Saxon “fall”? And I remembered Borges meditating in a similar vein about the advantages of writing in English. No doubt, the major Spanish-language writers today are less provincial than their English-speaking peers who hardly ponder the subtle shades of meaning offered them by the Castilian tongue . . . Yet isn’t this what Goethe’s world literature is all about: the creative contact between the intensely local and universal relevance and responsibility? García Márquez will stop in Colombia on his way back to Barcelona from Mexico. He promised to return to Oklahoma because of its spaces, silence and simple sentences.

University of Oklahoma

From Books Abroad 47, no. 3 (Summer 1973), 439–440, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40127313

A Review of Vivir para contarla, by Edward Waters Hood

Gabriel García Márquez. Vivir para contarla. New York / Buenos Aires. Knopf / Sudamericana. 2002. 573/579 pages. $25. ISBN 1-4000-4106-6 / 950-07-2298-4

October 2002 was marked by the publication of Vivir para contarla (Eng. Living to Tell the Tale, 2003), the intensely anticipated first volume of Gabriel García Márquez’s memoirs. In this 579-page text (Argentine edition), the Colombian Nobel laureate recounts, with the brilliant imagination and stylistic virtuosity that have characterized his literary production, the first thirty years of his life, from his childhood in Aracataca to his first trip to Europe, in 1957, as a foreign correspondent for the Bogotá newspaper El Espectador. These years were highly influential in his development as a writer and in the creation of the fictional world of his early short stories and novels, the “Macondo” cycle.

General readers and literary critics familiar with García Márquez’s fictional, journalistic, and cinematic works will thoroughly enjoy this story. It is a text that can be read as a memoir or a fictional text, or an amalgam of the two forms. Its apparent generic autonomy as memoir is a sleight of hand; perhaps it can best be understood as part of the great textual world, unified in form and content, that this author has created throughout his career.

The book’s epigraph, “La vida no es la que uno vivió, sino la que uno recuerda y cómo la recuerda para contarla,” is revealing. In García Márquez’s view, the requirements of fiction and of a well-told tale take precedence over an empirical approach to writing, and fictional reality often attains authority over, and imposes itself upon, “reality. “ Despite this approach, the book documents well crucial events in García Márquez’s personal life and the social and political life of Colombia.

The author, who argues here that the short-story form is superior to the novel, begins the story of his life in medias res, recounting a trip he made with his mother to Aracataca in order to sell the family home there. This reencounter with the town of his childhood was pivotal in his development as a writer: it was the critical moment when he decided to consecrate his life to literature, and it provided him with the magical vision of reality he would later express in his fiction. In his words, in Aracataca, “No había una puerta, una grieta de un muro, un rastro humano que no tuviera dentro de mí una resonancia sobrenatural.”

As these memoirs recount early episodes in the author’s life, events that form the basis of his narrative work, it is not unusual for the reader to encounter herein reiterations of elements from his earlier novels and short stories. What is surprising here is the repeated intercalation of textual fragments taken directly from his renowned fictional works; for example, the following description of the “fiebre del banano” surrounding the arrival of the United Fruit Company in Aracataca is lifted verbatim from the first pages of La hojarasca: “En medio de aquel ventisquero de caras desconocidas, de toldos en la vía pública, de hombres cambiándose de ropa en la calle, de mujeres sentadas en los baúles con los paraguas abiertos, y de mulas y mulas y mulas muriéndose de hambre en las cuadras del hotel, los que habían llegado primero eran los últimos.” Readers will also recognize the techniques they have come to recognize as trademarks of García Márquez’s style, including the use of hyperbole, enumeration, alliteration, anaphora, and personification, along with a large dose of humor.

Vivir para contarla also contains a wealth of anecdotes from the author’s early life that he later developed into short stories and novels, and there is considerable discussion of the books and writers that have had the greatest influence on his vision of literature. Of particular note is the list of twenty-three books his friends, members of the famed Grupo de Barranquilla, sent him to read during a period of convalescence.

This wonderful first installment of Gabriel García Márquez’s memoirs, which ends with the author’s departure from Colombia for Europe with little sense of his own identity and fearful about conditions in his country and his uncertain future as a writer, is an open and incomplete text. This ending must be intentional: like Scheherazade, one of García Márquez’s greatest gifts has been his ability to exceed the tremendous expectations and hype surrounding his upcoming stories, and he has yet to disappoint his readers.

Edward Waters Hood

Northern Arizona University

From World Literature Today 77, no. 2 (July 2003), 75, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40158000

Editorial note: Two outstanding critical appreciations of García Márquez include Michael Palencia-Roth, “Gabriel García Márquez: Labyrinths of Love and History,” World Literature Today 65, no. 1 (Winter 1991), 54–58; and (in the context of an essay on Álvaro Mutis, García Márquez’s countryman and 2002 Neustadt Prize laureate) Gerald Martin, “Maqroll versus Macondo: The Exceptionality of Álvaro Mutis,” World Literature Today 77, no. 2 (July 2003), 23-27.